Drugs in Sport

It’s been a while since I’ve penned a controversial post. Experience (and my web stats) have shown me that the most popular posts on this website are either slightly controversial (curiouser and curiouser, selection news, and on skating at altitude) or to do with photography (photo gear, and the truth behind the shutter are the most viewed articles on this site). This post will likely fall into the former category. Those readers who have been paying attention know that I’ve been very close to elite sport for a very long time now. I’m also quite an enthusiast when it comes to things like mathematics, and reading academic journals… which is not so common these days among professional athletes. I feel that this combination allows me to speak with at least a little bit of authority on these matters.

First up, I should mention that I can’t prove in a legal sense, any of the accusations that I will inevitably make or imply. I don’t think I’m going to get into any trouble for saying any of this, although if I were ever to become famous for whatever reason, I may be called up on it. If that happens, I won’t back down. You see, you don’t have to believe anything that I say. You could write me off as an embittered ex-athlete, except if you actually knew me, you would know that I don’t really care enough about sport, especially my own achievement in it, to ever really feel embittered about it. I’m just calling it as I see it, and those who know me well, know that I don’t miss much.

The first thing one needs to understand when one approaches sport these days is that, beyond amateur community league sport, sport has very little to do with all that “faster, higher, stronger” nonsense that you get fed as a kid, and really falls more under the category of entertainment (NBC’s budget for the winter games was north of a billion dollars). That is not to say that elite professional athletes aren’t faster, don’t jump higher, or aren’t stronger than your everyday club badminton player for example. But being good at sport, and I mean very good, is an expensive undertaking and only within the framework of sport-as-entertainment can that level of performance be sustained.

The Olympic Games, supposedly the pinnacle of sport, is basically a huge show. I apologize to anyone who still has any illusions about the Olympics being an amateur competition, because it is not. With very few exceptions (curling, for example), pretty much everyone who goes to the Olympics does their sport full time. How can they afford to do this? Easy – they are paid to. Often it isn’t much, and I would be lying if I were to give the impression that all professional athletes live very comfortable lives, but the truth of the matter is that hardly anyone at the Olympics is an amateur. Would Pierre de Coubertin have disapproved of what the modern Olympic games have become? Probably. But in a strange way, the influx of money into sport that comes with professionalism has become a great equalizer in the world of sport. Prior to this, participants at the games were mostly very wealthy people who could afford the “spare time” required to train properly for the games.

But what does this have anything to do with drugs in sport? Well, if I gave you some growth hormone, or EPO and said “here, take this” you probably wouldn’t do it. Why wouldn’t you do it? Well, you’re messing with your endocrine system, the viscosity of your blood, you might get caught, and the side-effects might leave you sterile or give you a heart attack. In short, it’s a risky thing to do. Maybe you can find a doctor to supervise your performance-enhancing drug taking, well then it starts to get expensive. All things considered, taking performance enhancing drugs effectively is an extremely expensive (the drugs themselves are also costly) and dangerous thing to do. In order for someone to make that kind of investment, and to take those kinds of risks, a very large reward is needed as incentive. So here’s where the money-in-sport equation starts to become relevant.

“Each one of the riders on the tour draws a salary of at least one million euros”

Take professional cycling as an example. The Tour de France is one of the most grueling and challenging sporting events ever dreamt up, and it is watched on TV by people all over the world. Because of this TV coverage, there is a huge potential for advertising on riders’ jerseys and, as a result of this, large and very well-run, and well-funded professional teams have formed who compete with each other. Each one of those bikes costs upwards of $10,000, and they have lots of bikes per rider for all kinds of situations and eventualities. Each one of the riders on the tour draws a salary of at least one million euros on top of all the free gear. Think about that for a second – one million euros a year just to get on a bike and ride all day. Riding is also fairly low-impact so a good rider can expect to have a career in excess of ten years. Six or seven good rides in le Tour during that time, and you may never have to worry about finances for the rest of your life. Does that create a strong incentive to dope? I would think so… and I would go so far as to say that everyone on the tour does it.

Don’t these people get tested? Of course they do, they just don’t get caught. The doping on the tour is systematic and the team doctors supervise it. Of course they do. Erythropoietin – better known as EPO increases your blood’s ability to carry oxygen, an obvious advantage in an endurance sport like road cycling. It also thickens the blood. I’m not exactly an endurance athlete (in fact, most would call me a “specialist sprinter”) and my resting heart rate is in the low 40s, a career endurance athlete would likely have a resting heart rate in the mid-to-low 30s. Think about that – that’s a beat every two seconds. Under normal blood pressure, if you’re running a beat every two seconds, if your blood is unusually thick, then it has a tendency to clot. If one of those clots ends up in a coronary artery, then your heart will stop. One of the roles of the team doctors these days is to wake up riders in the middle of the night, and get them onto the stationary bikes to keep their heart rates up to stop them from dying in their sleep. Of course, now that there’s a test for EPO, nobody uses it anymore, and another similar drug has almost certainly replaced it.

The trouble with tests is that you can only test for a known substance (you can obviously detect anything, but the quantities are so small that it would be impossible to show that any old anomaly was a performance-enhancing drug). Marion Jones doped for years on a designer steroid known as “The Clear” (tetrahydrogestrinone) and nobody would have ever known about it except that a sample of the stuff was turned in by a bitter coach and so a test was developed for it. If that sample had never been turned in, it would still be in use today, and remain undetectable. There is a very good chance that there are more designer steroids out there which may never be detected.

Does this ruin the world of sport? I don’t think so. It just makes it a little bit different. A lot of kids grow up thinking that being really good at sport is just a matter of training hard and being dedicated. When you slowly make your way up the ranks of elite sport, there is a point where you realize that this isn’t true, and a myriad of factors that are completely outside your control, like genetics, play a huge role in determining how successful you ultimately are at sport. Despite what he says, it is almost certainly true that Lance Armstrong, along with everyone who rides in the tour, is doped up to the eyeballs. That doesn’t make his achievement of winning seven tours any less remarkable. He still had to train very hard and be a bit of a genetic freak of nature to do all of those things. His battle with cancer is no less inspiring. There’s nothing “unfair” about the doping that goes on in the tour, because it is still very much a level playing field because everyone does it.

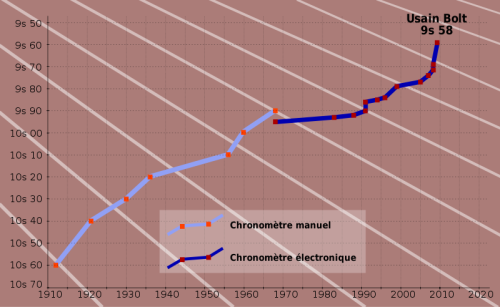

So which sports are rife with doping and which aren’t? As it is with most things these days, you have to follow the money. Anything that appears in the Olympics is a likely candidate because the exposure that the Olympics guarantee will raise the kind of money that makes doping “worth” it. Track and field is a good example of a sport in which not-doping places you at a severe disadvantage. Take Usain Bolt for example. I would contend that his world records are not “clean”. Of course, I don’t think any world records have been clean since the late 80s when athletics really started to become very financially lucrative because of sponsorships, endorsements, and the IAAF world athletics tour.

As a side note, when viewing word record progressions in sports, it is always interesting to note that whenever a test is developed for a significant and widely used drug, such as testosterone, the frequency of world records suddenly drops, but always eventually catches up. The year before a sex test was developed for women there were about 15 women who ran 1500m in under 4 minutes. The year after the test was developed, that number dropped to 2.

The Jamaican case is an especially good example of doping evasion. One of the major advances in anti-doping efforts was the introduction of out of competition testing. Prior to this, people would dope for 3.9 years and then be “clean” for the Olympics (they often didn’t bother being clean for anything else – Carl Lewis, gold medalist in 1988 after Ben Johnson’s famous disqualification himself failed three tests in the two months prior to the Seoul Olympics). Out of competition testing involves randomly showing up to an athletes home or training facility and demanding a urine sample. This generally works very well, making it almost impossible to systematically take any detectable drugs. However, there is a flaw in the system – WADA, the world ant-doping agency requires respective countries’ IOCs to ensure that the testing is carried out. Countries like the USA have USADA and Australia has ASDA to conduct their out of competition testing. However, countries like Jamaica don’t have such an agency.

Again, I emphasize that I am not taking away from any of these guys’ achievements. In a perfect world where nobody doped, Usain Bolt would probably still have won his gold medals and set his world records. Those records would have been a little slower, sure, but no less impressive. The margins might also have not been so great because the absence of out-of-competition testing gives the Jamaicans a distinct advantage over their counterparts from other countries. One might be tempted to think that this advantage should be huge, and that the playing field is no longer level, but this isn’t quite true. Firstly, countries that have their own out of competition testing programs also tend to be a bit wealthier, and thus have better access to better drugs. Secondly, out of competition testing programs aren’t without their flaws.

Speed skaters get tested a lot. As do badminton players, I’m told. That’s because they don’t dope. I’ll get to why that is the case shortly. But my point here is that an out of competition testing program sets itself a goal of a certain number of tests. It them measures its “success” by how many positive tests it gets. Often (and I cannot prove this, but I’m pretty certain that it happens) when the doping is systematic and state-sanctioned, the “random” anti-doping program will be timed in such a way as to coincide with periods in a doping program where an athlete won’t test positive. During times when an athlete will test positive, the anti-doping agency will simply test other athletes. This way, they can still get to the end of their month or whatever, and say that they have a certain number of negative tests. Taking the randomness out of the system effectively renders it useless, and does so in a way that makes it seem like it still works.

So why don’t badminton players and speed skaters dope? Like I said before, not every elite athlete leads a luxurious life of multi-million dollar endorsements. Many sports also don’t benefit a great deal from doping. The greatest advantages to be had are in sports which require endurance, and muscle bulk. Badminton is great sport, and one must be quite fit to play it at the elite level, but the potential gains that doping would have on badminton, while they do exist, are probably not great enough to make the risks worth it.

Speed skating is an interesting example, and one that I’ve thought about for a while (for obvious reasons). I’m actually pretty sure that doping does exist in speed skating (apart from the obvious case of Claudia Pechstein) but that it is not very widespread. Curiously, Pechstein was only caught because of the introduction of the Biological Passport which doesn’t directly detect the presence of illegal substances in the blood, but rather it looks at the parameters of certain biological markers and sees how much they fluctuate over time. Strangely enough, Pechstein managed to get an injunction which allowed her to do one race at the Salt Lake City world cup in December 2009 (where I was also present, photos here) and, not surprisingly, she failed to qualify for the Vancouver 2010 games.

I mentioned before that riders on the tour earn upwards of a million euros a year, which over a long career can be a pretty strong incentive to dope. There are probably one, maybe two speed skaters in the world who make that kind of money. Everyone else kind of just scrapes by. The other factor at work here is income inequality. Speed skaters, by necessity, almost always come from fairly wealthy countries. This is because it is an expensive sport – the skates are expensive, ice time is expensive, the suits we wear are expensive. To even be able to compete, a huge amount of money needs to be invested first, over a long amount of time. The facilities also present a problem – I don’t know of a single long track in the world that doesn’t operate at a loss. Those things are extremely expensive to run, and most do it with government support, and a government has to be fairly wealthy in order to support that kind of sport.

This is why income inequality is important – it all comes down to a fairly simple equation: on the one hand, you have the enormous cost and risks, both legally and health-wise associated with taking drugs, and on the other you have the potential financial gain that may result from success gained by taking drugs. Most of the world’s speed skaters come from the Netherlands or Norway, both are very wealthy countries with high standards of living. In other words, it’s going to take huge amounts of money to make them want to dope, and while there is a lot of money in skating, there isn’t enough for that. Speed skating is also quite popular in many former eastern-bloc countries, and while the argument for doping in those cases is more plausible, it is still unlikely because, without the huge inequalities that used to exist, and without the massive state-driven systematic doping machine (whose last “product” was a young Claudia Pechstein) poor kids who want to make it in life have much better options (like internet scams) and the people who end up in speed skating tend to come from relatively wealthy families.

Contrast that to running, where athletes can come from very poor countries, and where entry-level equipment is very cheap. Compare a kid who is a talented runner in Jamaica with one from Norway. Who’s going to take the huge risks? Who stands to go from a life of poverty to one of unimaginable wealth? Who is going to receive help from their own sport’s governing bodies with systematic doping? Keeping this all in mind, I’m actually very optimistic about the eventual demise of systematic doping. Because in a perfect world, the monetary incentives just won’t be strong enough for people to want to take the risks. The only people left who will dope will be the crazy sociopathic people whose desire to win outweighs their sanity (at which point sport will obviously be only for entertainment purposes). Of course, such a world is still a very long way off. In the meantime, we’ll still have to put up with similarly crazy people who defend doping by being either ignorant of the way sport works (“but doping can only affect a 3% gain in performance at most”… uh duh, a 3m margin in a 100m race is kind of a big deal) or ignorant of the health risks involved, keeping in mind that those most at risk are also the poorest and least able to protect themselves from those risks.

At the moment, a lot of people “love” sport, but I suspect it is only because sport is their ticket out of poverty, which is what ultimately opens the door to the possibility of doping. In an ideal world, even though Olympic athletes would still be professionals, and would probably get fairly decent pay (as entertainers), it wouldn’t be so much that it would necessitate the need for performance enhancing drugs. In that sense at least, they would be doing it simply because they love the sport, which is where the word “amateur” originally comes from.

Further reading: “Positive” by Werner Reiterer, my own review here.

What gets me is government spending on sport. The people who participate in and are otherwise involved in the sports that aren’t commercially viable are overwhelmingly upper middle to ruling class. Government spend on these sports is middle class welfare.

The trouble with sport is that it’s very expensive. You could approach from the public health angle, but if you do, then elite sport shouldn’t get any funding at all.

I obviously quite like elite sport, but where should its funding come from? Advertising revenue from TV is probably your best bet. But less “visible” sports (like handball, which gets almost no coverage in Australia) would be hard to justify.

In the end, I don’t think it’s welfare at all. The athletes are merely pawns in a huge international penis-measuring contest where governments try to outspend each other for gold medals and glory. Drugs are just an easy solution – an illegal “additive” in the sports machine.