Bad Advice Part 3: How To Buy A Camera

Photography’s a wonderful thing, and with the ubiquity of digital cameras, it has become more accessible to more people than ever before. Cameras are literally everywhere, in people’s phones, built into their computers, and watching over busy street corners. Of course, not all cameras are equal, and image quality still counts for a lot, both in the technical sense as well as the artistic sense. For some unknown reason, I am often asked to advise people on buying cameras. Some of it is probably down to the fact that I am a bit of a gadget-freak, with a good memory and ability to recall the specifications of a wide range of camera models, saving them the time it takes to look these things up on wonderful websites like dpreview. The other reason is probably because they consider me to be a somewhat decent photographer, and that somehow this combination would help translate their photographic needs to a sound technical choice.

I’ve divided this article into two distinct sections. In the first section, I’ve detailed the process of searching for a camera – this is the part which should still be useful and relevant even in 10 years’ time. These are the basic steps which you should go through, and the questions you should be asking yourself when you go to buy a camera. The second section deals with specifics – here I will list a number of stand-out cameras which are currently available, their various advantages and disadvantages, and which kinds of photographers they would be best-suited for. This is not an exhaustive list, and I give zero advice to professional-level photographers, since if they are professionals, then they probably know enough about the subject to be able to make the decision without my help. It will be very interesting to look back on this second section in a few years’ time, in much the same way that we are amused by the above photo of me holding a very old (analogue) rangefinder camera from the early 80s.

The Process

The first question you should ask yourself is “what am I using this camera for?”. Basically, you need to really think about what kinds of photos you’re going to take, and under what kinds of conditions. If you mostly use a camera to take portraits, then your priorities when choosing one are going to be different compared to if you use your camera to take pictures of sports. Although the technology moves at a staggeringly fast pace, and the cost of cameras seems to always come down, unless you have very large sums of money to spend on camera gear, then everything is about compromises.

The second question you should ask yourself is “how much am I willing to spend?”. Some people believe that this is the first question that you should ask, but I don’t because I prioritise getting the right camera for the job over getting the best possible value for money. As a general rule though, when you walk into a camera shop the first thing you should mention is a price which is slightly lower than the price you have in mind.

As a general rule though, when you walk into a camera shop the first thing you should mention is a price which is slightly lower than the price you have in mind.

At any given price point, there are going to be many different cameras, and it is never obvious which one is “best”. Of course, a camera which is the best for my purposes might not be the best for yours, and this is what makes the process difficult. Everyone likes to say, I want a camera that takes “good pictures”, but what you’re photographing and how you photograph it will have a big impact on the quality of those pictures, and which camera you choose will determine the “how”.

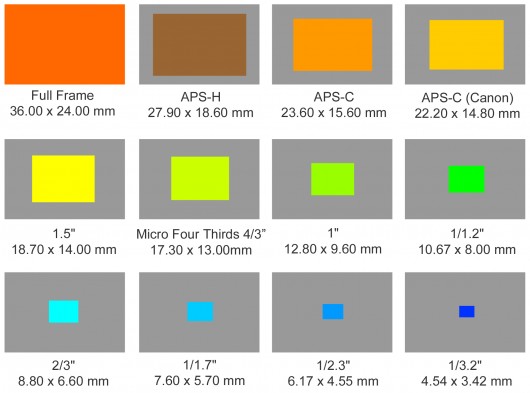

Image quality in a strictly technical sense comes down to two things – the quality of your lens, and the size of your image sensor. In a previous post where I give tips to beginner photographers, I said that it is all about the light. Well, your lens and your image sensor are the camera’s direct interface with the light. A good lens will focus more light more accurately onto the image sensor, and a larger image sensor will gather more light – simple. Unsurprisingly, the biggest variations in the price of cameras comes from changing the quality of the lens, and changing the size of the image sensor – you get what you pay for. 1

Every other parameter that is compromised in the quest for your best camera at any given price point is inextricably tied to those two variables – the lens and the sensor. If you need a faster camera, then the size of the image sensor usually has to come down (a larger sensor usually has to process more information). And of course, there’s the camera-human interface, and preferences for that will vary from person to person.

Table of image sensor sizes

Cameras with larger sensors tend to be larger and heavier. Despite the name, there are cameras with sensors larger than “full frame’, and these are called medium format cameras (there are even ‘large format’ cameras, but no digital ones as far as I’m aware). I’m not going to talk about them, because if you have the kind of money to spend on a camera where you can be seriously considering the purchase of a medium format camera, then (once again) you do not need my advice in picking a camera.

As a general rule, I consider any camera with a sensor smaller than 1″ to be not worth the trouble – size does matter. This is because, if you’re going to go smaller, then the difference between those images and those taken with a good camera phone isn’t going to be much. Even with sensor technology advancing the way it is now, you’re asking too much from the lens to be able to gather a lot of light and focus it accurately onto the image sensor. There are other technical considerations which affect image quality which I won’t go into here, but suffice to say that I would never buy a camera with an image sensor smaller than 1″ for reasons of image quality.

I consider any camera with a sensor smaller than 1″ to be not worth the trouble – size matters.

What next? Thankfully the ‘megapixel arms race’ which camera manufacturers were having in the mid-naughties has finally stopped. More megapixels isn’t necessarily better – anything above 12 will do the trick. Other parameters which camera shops used to use to sell you bad cameras were things like zoom range (5x optical zoom!), and strange novel features like highlighting a single colour in an otherwise black and white picture. The zoom range thing has evolved into a more meaningful measure, that is instead of quoting the multiplication factor between the lens’ widest setting and it’s longest, manufacturers now give the zoom range in terms of (35mm-equivalent) focal lengths, which is actually very useful. This is one of the first things you need to consider, and the way you consider it will have a lot to do with what you are photographing. Focal lengths can range all the way from 14mm at the wide end, up to 400mm (or more) at the long end.

For street photographers and landscape photographers, wide angle lenses are the way to go. Make sure the zoom range on the camera you choose covers a reasonable chunk of the wide territory (its widest focal length should be 28mm or less), or if you get a camera that can take different lenses, make sure you get a wide one. For interchangeable lens cameras, it is worth remembering that while zoom lenses are obviously very versatile, you will always get better optical quality from a fixed focal length lens, sometimes called ‘prime’ lenses. For most other applications, the most useful focal lengths lie between 35mm and 60mm (cheap fixed-lens film cameras of the bad old days used to almost always come with a 35mm lens). If you take a lot of portraits, the focal lengths from 50mm-135mm are the most useful to you. If you’re into sports, you usually want very long lenses because you’re not ordinarily allowed to be very close to the action so 200m-600mm is what you’re after. Those lenses are very big and heavy (and expensive). For things like birdwatching and nature photography, you pretty much want a telescope on the end of your camera – 400mm and up.

Quick Diversion Re: Focal Lengths

Everyone talks about zooms, but what we should be talking about focal lengths. If your zoom lens covers the range of 24mm-120mm then it’s a 5x zoom. If a lens covered the range of 100mm-500mm, it is also a 5x zoom, but both of these lenses would be VERY different.

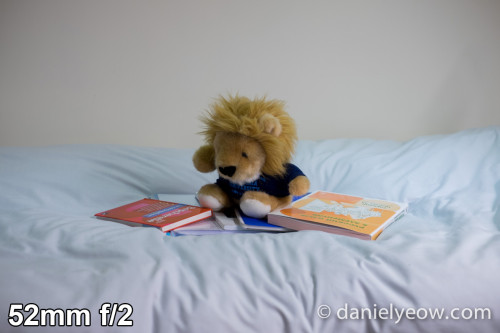

Below is a rough guide to what different focal lengths “see”. I’m standing about 2m from the lion on my bed, which is a standard single bed.

Anything wider than about 35mm is considered “wide angle”. It used to be standard to include one fixed focal length lens on a cheap camera, and that focal length used to be 35mm. When digital point-and-shoot cameras became a thing, this was the starting point for most zoom lenses, because camera manufactures realised (correctly) that the vast majority of photos taken with their zoom lenses would be at the widest setting – i.e. not zoomed at all – people are lazy. Recently, it has become popular to begin the zoom range at 27mm or 28mm, probably to accommodate the tourist-landscape photographer set (which is a significant reason behind why most people buy a camera), and also so that you can fit more people into a selfie.

35mm is considered ‘standard’ or ‘wide-standard’. Back in the bad old days when hardly anyone had cameras, and you usually only had one lens, it was usually either a 35mm or a 50mm lens. It is said that journalists tended towards the 35mm. When I walk around with a camera with only one focal length, this is it.

This is another ‘standard’ focal length. Focal lengths between 40mm and 50mm are widely used because they are supposed to simulate the angle of view of the human eye (it depends a bit on what you’re looking at, but this is generally true). Wide-angle photos look spectacular, and that is often because they contain a lot of information that you wouldn’t normally see in your field of view, the idea behind a 50mm lens is that it closely simulates a ‘natural’ field of view.

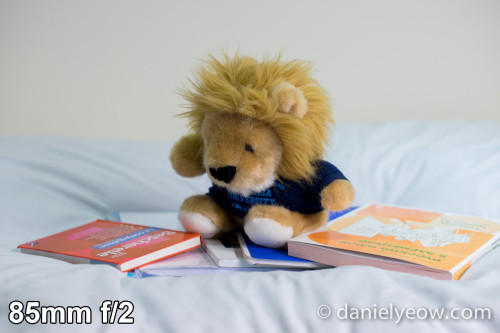

Getting towards the longer end of the focal lengths, 85mm is considered good for portraits. What I said before about natural fields of view is generally true, but when you’re looking at something like a face, you’re more ‘focused’ on a small part of what your eye is seeing (the face, presumably). What you have to remember about photography is that nothing about it is particularly ‘natural’ – you’re artificially framing some part of the world that you perceive from a certain perspective. If you’re focusing on a face, then you compose your photo so that the face dominates it, and longer focal lengths are one common way of doing it.

Longer focal lengths can also be used for portraits, and are also good for sports. With sports, you don’t normally get to be VERY close to the action. Even front row seats at events can be as far as 50m away from where things are happening, and sometimes more. You can always crop your photo, but that results in a sacrifice in resolution and image quality.

That is why sports photographers are always carting around these huge lenses which are basically very long focal lengths combined with large maximum apertures (small f-numbers) which allow for faster shutter speeds to freeze the action.

Even when you have the freedom to be as close or as far away as you want from a subject, the focal length is important. Consider the following two photographs which both have the lion taking up a similar chunk of the frame, but observe how the different focal lengths have an impact to how he ‘looks’.

In both photos, the lion takes up a similar proportion of the frame, but the angle of view, in particular with its effect on the background make both portraits look very different. Keep this in mind the next time you look at portraits of people in magazines.

Prioritise

There are always going to be tradeoffs. You as the buyer has to decide what is most important for you, and to what degree. If you only care about one thing, then that generally makes the decision very easy. For example, if you only cared about image quality, then you buy the camera with the largest sensor that you can afford on your budget. Of course, there’s more to it than that, and most people take photos for reasons other than pouring over the images on a computer screen and inspecting the individual pixels to see how sharp the image is.

Focal length range, and in particular whether or not you want to have just one lens, or have a camera which is able to change lenses can be very important. The ‘speed’ of the camera, which is a combination of how fast the lens is, and how quickly the camera can process images from the sensor. Nikon’s flagship D4s for example can shoot at 11 frames per second while tracking auto focus and auto exposure at the same time (that is mind-blowingly fast) but it also costs 6,500 USD for the body alone (without lenses). The size of the camera may also be an important factor – big DSLR cameras aren’t always welcome in certain places, while in other situations a large professional-looking camera can open doors. Smaller cameras are also less-intimidating for portrait work (you don’t always get to work with experienced models – most people get nervous in front of a large camera).

Lastly, the ergonomics must never be overlooked. You’re going to use your camera, and to really be able to use it, it will need to ‘fit’ comfortably in your hand. The controls that you need frequently should be within easy reach, the back of the camera shouldn’t be filled with an overwhelming array of buttons – to a professional photographer, the back of a professional DSLR screams ‘convenience and control’, whereas to a beginner photographer, the message is more ‘confusion and panic’. I tell everyone this – even if you intend to buy online, go to a shop and pick up the camera in your hands and play with it. Make sure that when you do, you think to yourself ‘I can see myself using this camera’ and be ok with that.

Buying Procedure

Walking into a camera shop and saying “I’d like to buy a camera” isn’t going to help anyone (although it is certainly amusing, as I’ve discovered on numerous occasions). Start by telling them approximately how much you’d like to spend, or telling them a number which is four fifths of what you would like to spend. Then tell them what you would like to use it for. At this point, they’ll probably suggest a few models to you, and depending on how knowledgable they are, these may or may not be a good starting point. At specialist camera shops (like B&H or Adorama in NYC, for example) you’re likely to get pretty good advice, whereas in a shop where they also sell fridges and microwaves, you probably won’t.

Do some research on the internet beforehand at websites like dpreview, and if you’re considering cameras which can change lenses, then also consider reading lens reviews on sites like photozone (although these are aimed at more experienced photographers). If you can at least seem knowledgable to the salesperson, they’re far less likely to try to rip you off, and they’ll treat you(r intelligence) with a little more respect. The advantage with shops is that there’s more flexibility on prices compared to the internet, and they will often throw in little extras like screen protectors and memory cards. Checking the internet beforehand though is always a good idea to get an general feel for how much the different cameras cost. It’s not unusual to run into a really good deal in a shop if they’re trying to clear certain stock, or if there are special offers from a particular manufacturer.

A nice strategy is to ask for the ‘old’ model. The camera industry has matured to the point where almost every camera out today is an Nth iteration of a previous model. Often you will be recommended a camera slightly above your price range that you’ll really like (those sneaky salesmen), if you can’t afford it, ask them if they have the previous model. The previous model will have fewer features, but often those features will be things that you don’t care about (although sometimes they ARE things that you care about). Previous models are also difficult to sell and so will usually represent good value for money (for this reason, previous models are often sold out).

Shop around. This will be difficult if you don’t live in a big city. Shopping around is not just useful to try and get a good price on any given item, it is also good for getting a feel for what shops are trying to push, and what kinds of discounts are available. Also if you’re looking for either a very new, or very old model, chances are you’ll need to visit a few shops before you find one in stock.

Tips and Trends

Camera technology, like most technology these days, advances at a staggeringly fast rate – keep this in mind. Things which are dependent on software will change the fastest, so things like the apps which come with the camera, and software filters which inexplicably make your photos look like they were taken with a cheap plastic camera (thanks hipsters). Next are more hard-wired technologies, like image sensors, autofocus algorithms, and the resolution of screens and viewfinders. Slowest to move are ‘hard’ technologies – lens optics for example. Roger Cicala at lensrentals has written numerous articles on the history of lens development for cameras which I won’t repeat here except to recommend everyone to read them. The bottom line is that the lenses in cameras today are pretty much all descendants of six basic lens designs, the last one of which was invented in the 1930s – in other words lens technology moves relatively slowly, even in the age of computer-aided lens design.

What does this mean for our purchase? Obviously you want a camera that isn’t obsolete within a few years. Luckily this isn’t likely to happen, now that all camera manufacturers have settled on using JPG as their default compressed image format, and SD and CF memory cards. The megapixel race has also finally abated. My note about technological advancement only really applies if you intend to purchase an interchangeable-lens camera (ILC). If that is the case, if you’re trying to decide whether or not to spend more money on a good camera body, or on a good lens or lenses, then definitely go with better lenses, especially if you plan on making a long term commitment to your hobby.

The first professional digital cameras were basically professional film-based SLR cameras with an digital image sensor put in place of where the film would have been – this general formula hasn’t changed.

You may have heard a lot lately about so-called ‘mirrorless’ cameras. These are named because they lack the ‘reflex mirror’ which is where the ‘R’ in SLR comes from (single lens reflex). SLR cameras (DSLR just means ‘digital’) are still, generally speaking, better cameras. They’ll give you better image quality, they have better lenses available to them, and they focus faster. The reason for this is because they are a very mature technology – they’ve been around forever – since before the 1900s, and in their ‘modern’ form since about the 1940s. The first professional digital cameras were basically professional film-based SLR cameras with an digital image sensor put in place of where the film would have been – this general formula hasn’t changed.

The major advantage of an SLR camera is that, through a prism and via a mirror, you see the exact image which will be captured on film or the sensor. Of course, with digital sensors and screens, this isn’t an advantage anymore. So why do we stick with the old formula? First there’s the viewfinder – framing a photo with the screen is all very well, but in bad light, or in very bright sunlight these screens don’t always work very well, so a viewfinder is preferable and until recently an optical viewfinder was the only type of viewfinder which gave a very immediate connection between the photographer and the subject (screens and electronic viewfinders typically have a small but noticeable delay). Then there’s the auto focus – the mirror allows a separate, dedicated auto focus mechanism to focus the camera before the mirror is flipped up and the image hits the sensor, until recently the only way to autofocus straight onto a sensor was by using slower contrast-detect algorithms.

It is my opinion that mirrorless cameras will eventually replace SLR-type cameras in all important segments of the digital imaging market and that in 10 years you’ll only have a camera with a reflex mirror if you’re a hipster.

These days, the technology has come a long way, and mirrorless cameras are very nearly the equal of DSLRs, and come with their own advantages. They’re almost always smaller, since they don’t have that awkward mirror taking up space between the lens and the sensor, they are also generally faster since, again, they don’t have to flip the mirror up every time a photo is taken. And recently, importantly, electronic viewfinder technology has advanced to the point where there is almost no detectable delay between subject and viewfinder, even in low light. It is my opinion that mirrorless cameras will eventually replace SLR-type cameras in all important segments of the digital imaging market and that in 10 years you’ll only have a camera with a reflex mirror if you’re a hipster.

Lastly, one of the most recent trends is for cameras to come with built-in WiFi. Pretty much any camera that came out within the year has it. At best, it allows a user to connect to the camera via smartphone and control the camera remotely, and even view what the camera can see, at the very least, you can upload/download photos from the camera to your smartphone for immediate uploading to instagram/facebook/twitter. I will say that I’ve used this feature a lot, and that it has been very useful, but I wouldn’t recommend anyone base a decision to buy a camera on whether this feature is included. There are many alternatives to this, including “eye-fi” memory cards which themselves have wifi capability, as well as simply plugging a card reader into your smartphone or tablet (clumsy as that may be). Eventually, every camera will be released with wifi, just because it’s so easy to add at very little cost, and there’s no tradeoff with any other feature.

The Cameras

First, the compact cameras. These are pocketable cameras which don’t look like serious cameras but in the right hands can take seriously good photos. Buy these if you’re on a very tight budget, or if you’re trying to be stealthy (a news photographer in a no-press-allowed zone for example), or if you’re a pro and simply want a backup camera to have in your pocket/bag on those (many) days when you don’t feel like carrying your huge heavy professional camera around. Not long ago, it wasn’t possible to get a compact camera with a decent-sized image sensor, and I had to contend with cameras like the Panasonic LX7, and Canon S120 which only have 1/1.7″ sensors. But now, there are a decent number to choose from, and which one you choose will depend a little on your photographic priorities.

I will introduce each camera with a photo, and give a short paragraph about it including a list of pros and cons. For more detailed specifications and reviews, I’ll link the camera name to its page on dpreview.

This is the Sony RX100 (3). It is the third iteration of this camera, and each iteration has been significantly different from the previous one (notice I didn’t say ‘better’). The sensor size is 1″ which I consider the bare minimum for image quality. I love it because it looks exactly like any old point-and-shoot camera and is simple to just pick up and use. To have fit a lens with such a useful focal range (24mm-70mm) into this small a camera AND put a 1″ sensor in it is basically engineering magic. It also includes a built-in flash and pop-up viewfinder. It can be pricey, but as I mentioned before there are now two previous iterations which will be cheaper since shops will be trying to get rid of them. The RX100 (2) has no pop-up viewfinder, and its screen only flips up 90 degrees and down 45 degrees (the current model flips up a full 180 for easier selfies), and the RX100 (1) has no WiFi and its screen doesn’t flip at all.

Pros: Unbelievably small, good lens-sensor combination, looks and works just like cheaper (less-intimidating) comapct cameras Cons: Expensive, Not much manual control

The Ricoh GR you will recognise from a review that I wrote not very long ago. The big standout feature of this camera is that it has an APS-C sized sensor – that’s the same size sensor as you get in most DSLRs. The tradeoff is that the lens does not zoom – it only has one focal length, and that is a very versatile 28mm. This is the camera that lives in my bag all the time. It is pocketable and looks like every other compact point-and-shoot. In fact, the surface finish is such that it looks like a slightly old and not-so-good compact camera. Ricoh have toyed with the concept of a professional-grade compact camera for a while now, but this is the first and so far only one to really hit the mark (yes, the photos that this thing takes are professional quality). The others simply didn’t have large enough image sensors. It doesn’t bother me at all that it only has one focal length, and being a camera designed for pros, its control layout (the buttons and dials) is one of the best I’ve ever used (most control layouts on compact cameras involve digging into menus on the screen for ages to find the settings you want to change). Nikon makes an identically-specced camera called the Coolpix A which costs more, and does less.

Pros: Unbelievably small, ‘proper’-sized sensor, excellent control layout, Cons: Expensive, only one focal length, no viewfinder

Another camera from Sony, the RX1. There is a variant of this model called the RX1R which is identical in every way except that it removes the anti-aliasing filter.2 If you know what this is, then great, and if not, don’t worry because you won’t notice the difference in your photos (it makes a more noticeable difference if you shoot a lot of video). This is a very special camera because while compact (it’s on the larger side of things – only ‘pocketable’ if you have very large pockets) it contains a full-frame image sensor. Paired with this image sensor is a 35mm fixed focal length lens (with a maximum aperture of f/2). This amazing camera also comes with an amazing price tag – it is more expensive than some very decent DSLR cameras out there (in fact, I’m pretty sure it’s the most expensive camera I’ve listed). Honestly, if it were 2/3 its current price, I would have one. Sadly it isn’t, and sony has also seen fit to take a bit of the shine off such a miraculous feat of engineering by giving it the control layout of an amateur’s compact camera. I would redesign this camera with a flash that can be turned upwards to ‘bounce’ off the ceiling (giving more even light spread) and replace the PASM dial with a shutter speed dial, thereby giving it a manual shutter speed dial and a manual aperture dial – the two most frequently adjusted settings for a pro.

Pros: Full frame sensor in unbelievably small package, high quality lens with dedicated aperture ring, really good video quality Cons: Way too expensive, poorly-thought-out controls

Panasonic and Olympus were the first manufacturers to make mirrorless interchangeable lens cameras, and their cameras have mostly filled the ‘bridge’ category (the bridge is between compact cameras and SLR cameras). Their standard is called “micro 4/3” after the size of their image sensor. While not as big as full frame or APS-C, it is still large enough to produce excellent results. This is the Panasonic GM1, probably the smallest decent interchangeable lens camera out there (there are others, like the Samsung NX mini, but the lenses aren’t great and the sensor is much smaller). This camera comes with a kit lens which is similarly diminutive and covers a useful focal range (24mm-65mm), and of course you have the option of mounting any of the wide selection of micro 4/3 lenses manufactured by either Olympus or Panasonic.

Pros: Small package, great kit lens, access to a huge ecosystem of lenses, Cons: No viewfinder, not very fast, poor battery life

A relatively late entry into the mirrorless market is well-known camera manufacturer Nikon. They’ve decided to go with the 1″ sized sensor which I thought was an unusual choice when I first heard it. Out of all the Nikon 1 series cameras, the J-series is the most well-rounded. Out of the cameras mentioned so far, the Nikon is the least outstanding in any particular aspect, but it does do everything quite well. For those on a tight budget, it is also one of the cheapest to choose from without having to sacrifice image quality. The kit lenses are decent covering 27mm-80mm, they all come with a built-in flash, and can shoot surprisingly fast (10 frames per second). The latest incarnation is the J4, but the J3, J2, and even the J1 are very decent cameras which can be had for less than any of the cameras mentioned above. Sadly, the lens ecosystem isn’t huge yet and I’m not totally sure that it will ever become huge. Like the Sony RX100, these cameras were designed for people upgrading from compact cameras, so the control layout is very simple and unintimidating.

Pros: cheap, fast, well-rounded, easy to use, available in many colours, Cons: poor selection of lenses, no standout features, no viewfinder.

Next up we have medium-sized cameras, most of which are of the interchangeable lens variety, but one of which isn’t. These are too large to be considered compact, or pocketable, but of course are much more capable cameras with features which are distinguished by more than “it’s amazing that they fit [insert feature here] into such a small camera”. We’re starting to properly get into the territory of ‘system’ cameras, where you’re not just considering the features of the camera body, but also the potential of the lens ecosystem of which two manufacturers dominate – Canon and Nikon.

In 2007 the Canon 400D became the first DSLR to sell for under 1000 USD. Now with all the competition not only from the usual suspects Nikon, Pentax, and occasionally Sony, there’s also genuine competition from mirrorless cameras. This has had the rather wonderful effect of driving the price of entry-level DSLRs down a lot. In fact, I’m pretty sure this is the cheapest medium-sized camera I’ve listed. Painstakingly conventional, the Nikon D3300 squeezes a lot of camera into a small package. A very decent kit lens, 1080/60p video 3, wifi, built-in flash, and an autofocus which is still faster than all but the very best mirrorless cameras out there, this is functionally-speaking probably the best value for money you’re going to get out of a camera anywhere. In addition, you get a camera which can access Nikon’s impressive array of lenses.

Pros: tried-and-true control layout, optical viewfinder, excellent image quality, fast auto focus, fully-featured, Cons: slow (5 frames per second), bulky, ‘cheap’ build quality

This medium-sized camera is surprisingly enough NOT an interchangeable lens camera. It is the quirky Sony RX10. The big selling point of this camera is its lens – covering 24mm-200mm at a constant maximum aperture of f/2.8. It achieves this by pairing it with a relatively small 1″ sensor, but that’s still a bigger sensor than one usually finds on these so-called ‘superzoom’ cameras (usually a 1/1.7″ or 1/2.3″ sensor). Just for a bit of comparison, there don’t currently exist constant aperture f/2.8 lenses that cover 24-200 anywhere else, and to get that kind of focal length coverage at the same maximum aperture on any of my current cameras, I would need two lenses, each of which cost more than this entire camera. The smaller sensor also allows for a fast rate of shooting (up to 10 frames per second) which makes this camera one of the cheapest decent options for shooting sports (long focal lengths, large maximum apertures, and fast shutter speeds). It is a little large, but it comes with a built-in flash, viewfinder and is weather-sealed.

Pros: really great lens, weather sealing, fast shooting speeds, Cons: bulky, expensive, small sensor for the price

The Olympus Pen was one of the first mirrorless cameras to be made and we are now up to the 5th (sort of) iteration, the Olympus E-P5. It is the most fully-featured of the Olympus pen cameras with 5-axis in-body (as opposed to in-lens) image stabilisation, as well as built-in wifi. You get access to all the wonderful 4/3 lenses of which there are many, and a few really good ones. Also, and importantly, if the P5 is too expensive, there’s the PL5, PM2, P3, PL3, PM1, and PL2 (if you can find one…) all of which are very capable cameras. With styling to match the old Olympus Pen-F cameras (which were also popular in their time) these cameras represent a statement about the photographer beyond mere functionality. It is important to note however, that even though the previous models are quite similar, one thing that has improved quite significantly in mirrorless cameras recently has been autofocus speeds – make sure you test the camera you want to buy in a shop before getting it to make sure the AF speed is up to your requirements.

Pros: fully featured, in-camera stabilisation, large lens ecosystem, many previous models for deal-hunting, stylish Cons: complex controls and configuration, no viewfinder

Fujifilm were very late to the party when it comes to interchangeable lens cameras, but they’ve caught up quickly. Previously one of the world’s largest suppliers of film and photo printing paper, they’ve stood quietly in the sidelines making cameras which have achieved a loyal following. Unbeknownst to many in the still-photography world, Fujifilm are a big player in the world of video lenses, in particular in the world of electronic news gathering so it was no surprise to me when Fuji’s X-mount lenses started to get rave reviews. Also unique to Fuji are its image sensors, instead of incorporating a ‘traditional’ Bayer filter array of red, green, and blue, filters, they have come up with their own ‘X-trans’ filter array (look it up if you’re interested) which, due to the fact that it is less regular and repetitive, allows the sensor to combat moiré without the use of an anti-aliasing filter. In English: the sensor is sharper than similarly specced sensors. And here, these great lenses and new sensor technology are available in a relatively affordable, and beautifully-styled camera – the Fujifilm X-M1

Pros: pro (APS-C) image sensor for a not-pro price, retro styling, great lenses, Cons: no viewfinder, small lens ecosystem (for now)

No list of this kind would be complete without a representative of the Sony NEX line. Ironically, Sony has now dropped the NEX label, and the newest model is the Sony Alpha a6000 (not to be confused with Sony’s alpha-line of SLR cameras). To their credit, Sony are not afraid to try new things and push boundaries that nobody thinks of pushing, the RX1, RX10, and RX100 are testament to that. The NEX cameras have put an APS-C sized sensor into a very compact package. The 16-50 power zoom lens which came out with the NEX-6 (the predecessor to this model) was compact enough that the camera and lens combination could fit into a large pocket when the thing was switched off. In my opinion, they hit the sweet spot with the previous generation’s NEX-6 and NEX-5 models – pick one up for a bargain if you can still find one in a shop. The new model, while slightly faster and slightly higher resolution than the old model, is equal or inferior in every other way. The Sony ILCs also suffer the problem of having a large ecosystem of lenses, but very few lenses that I would call ‘good’, which is a real pity. For this reason, many NEX owners (including myself) use their camera to mount lenses from other manufacturers via lens adapters (you can see this in action in my review of the Sony NEX-6).

Pros: Good large sensor in small camera body, fast, large product ecosystem, Cons: few good native lenses, feature set starting to get bloated, viewfinder resolution actually lower than previous model(!?)

Going a little further up the ladder I’ve (surprisingly) chosen the Canon 70D. A camera so good that it almost seems like a mistake. it borrows many features from the much more expensive Canon 7D and it introduces a number of innovations all on its own including an ability to autofocus quickly and accurately in ‘live view mode’ (which is ‘normal’ mode for a mirrorless camera). Unlike entry-level SLRs however, the 70D has much better build-quality (one of the few complaints I have of today’s entry-level SLRs) and a more prosumer-oriented feature set. It is probably also the very best digital still camera yet at replacing purpose-built consumer video cameras at shooting video (because of its auto focus system). To top it all off, it has a swivelling, fully-articulating screen, and can shoot at up to 7 frames per second. Basically, when you have this kind of money to spend on a camera (1000 USD, body only) then you’re not going to be disappointed, and only have to choose a camera which suits your personality, needs, and shooting style.

Pros: class-leading video autofocus, excellent control layout, massive selection of lenses, weather sealing, optical viewfinder, Cons: very bulky, relatively slow for the price

Fujifilm’s X-T1 represents the full maturation of mirrorless cameras. It sports the X-trans sensor I mentioned before with the X-M1, and has access to all the high quality Fujinon lenses, but the real killer feature in this camera is the viewfinder. This is the first mirrorless camera viewfinder which has no perceptible delay, making it basically on-par with an SLR’s optical viewfinder, and in many ways superior (when it’s dark, for example). The viewfinder is also huge, with an angle of view equivalent to that of professional full-frame SLR viewfinders. In terms of shooting experience, it has no match, and I do not say that lightly. Aside from being able to stare into a large, bright viewfinder, manual dials abound – for aperture, shutter speed, exposure compensation, as well as ISO (light sensitivity). Without turning the camera on and looking into the viewfinder (something I would have to do with my DSLRs) I can instantly see what settings are in use. I often shoot in aperture priority mode, so I turn the shutter dial to ‘A’ (for auto). Sometimes if I’m lazy, I’ll do the same for ISO. This camera is what all SLR cameras should be, and what mirrorless cameras should have been from the beginning. The shooting experience is more engaging and enjoyable – this is a camera designed for photographers. The autofocus is fast, and most of the buttons on the back of the camera are customisable. If you can afford this camera, then you should get it. Without question – I own much better cameras (like a Nikon D800), but this is the one I use most frequently. Sure there are cameras with comparable specs on paper, slightly faster autofocus on the Olympus OM-D M1 or Panasonic GX7 for example, but it’s the lenses, and especially the lens-sensor combination which really impress me. Fujifilm have taken a ‘gamble’ by focusing on the two most important things to image quality, and it’s paid off.

Pros: large bright viewfinder, fast autofocus, best control layout, solid all-metal construction, weather sealed, high quality lenses, small, Cons: not many lenses yet, poor battery life, not-great video quality

Lastly, one of the unsung heroes of the camera world – the Pentax K-3. With the major manufacturers Nikon and Canon rushing to abandon their high-end APS-C DSLR cameras in favour of similarly-priced but lower-specced full frame DSLRs, Pentax is left in the curious position of being the only manufacturer left making a high end, pro-oriented DSLR with an APS-C sized sensor. Indeed, it’s only real competition is the Fujifilm X-T1 which isn’t even technically an SLR. Solidly built and with ‘a button for everything’ approach to control layout, the K3 is a refined and mature piece of equipment in a mature segment of the camera market. It’s also one of the few pro-oriented cameras which have sensor-shake image stabilisation (the norm for this end of the market is for the lenses to provide image stabilisation). In addition, Pentax, having been around for so long, also has an extensive range (bettered only by Canon and Nikon) of lenses to choose from, some of them very good.

Pros: solid construction, large number of lenses to choose from, pro-specifications, optical viewfinder, in-camera sensor-based image stabilisation Cons: autofocus slow on older lenses, poor video quality, bulky, poor wifi implementation

Wrap Up

This is obviously not an exhaustive list, or even a comprehensive list of worthy cameras, just a few which have impressed me in recent times (meaning that I’ve seriously considered buying them, used them, or have actually bought them). There are some obvious omissions too, like the Panasonic G/GF/GH series cameras, the Canon G1X Mark II, and the Olympus EM-1/5/10, all of which are seriously good cameras, but all of which are, in my opinion, replaceable by cameras on this list. Further up the scale are what I would consider “pro” cameras, which are cameras that full-time photographers who make a living from their photography use as their primary weapon. The last two cameras on my list are already borderline-pro cameras. The basic idea with stopping my list here is that if you have the time and money to invest in a better camera than those listed here, then you probably know enough about photography not to need my advice on buying a camera. Conversely, if you don’t know enough about cameras and photography to know exactly what you need out of a camera and which cameras can give it to you, then you shouldn’t be buying cameras that are better than those listed here, even if you can afford it – you would be paying for functionality and features that you will either never use, or never appreciate.

The best camera is the one you have with you, because it’s the one that gets the shot.

Even when I bought my first DSLR – a Canon 400D back in 2007, it took me months of heavy use to learn how to fully-realise all of its utility. Something that everyone should keep in mind is that, in every aspect except build quality, today’s entry-level DSLR cameras are the equals of top-of-the-line professional film SLRs of the late 90s. If your photos are terrible, it is exceedingly unlikely that it is the camera’s fault. Even now, owning professional-level photo gear and a number of other cameras I keep for specialised niche purposes, most of the photos I take are with my Ricoh GR. The best camera is the one you have with you, because it’s the one that gets the shot.

I realise I’ve written a lot more text than I probably intended, and a little more than most people are willing to wade through in their quest to buy a camera, but I do get asked for advice on buying cameras a lot, and I thought it would be useful (at least for myself, if not for my friends in need) to write down my thoughts on the matter. If you’ve read this far, then hopefully you’re now as well-equipped as you can be to go out and purchase your own camera. Obviously, if you still need help, feel free to contact me, but we’ll have saved a lot of time having to explain many of these concepts to you. Once you’ve bought your shiny new camera, head over to my article aimed at beginner photographers, then have a little browse through the various other articles about photography scattered throughout this website. But most importantly, don’t forget to have fun. Good luck!

Footnotes

- There is one notable exception to this rule; the luxury German brand Leica. They are generally very high quality cameras, but are far too expensive for what they are. ↩

- An anti-aliasing filter is ordinarily placed just in front of the image sensor and blurs the image very slightly in order to prevent moiré in the image when rendering photos with repeating patterns or close parallel lines. ↩

- High definition video is defined by two numbers, the first one 1080 in this case refers to how many horizontal lines of resolution there are while the second number refers to the framerate in frames per second. The ‘p’ (or ‘i’) means progressive scan which is when each frame is represented by the full-resolution image (or interlaced scan when each frame alternates between the odd and even horizontal lines). 1080/30p is considered the minimum standard to be called “Full HD”. ↩

Leave a comment